“Whenever we beg for nuances, for our difference to be articulated, for more diversity and accuracy in how our communities are described, in the characters written for ‘black’ actors on stage, on television, or in film, our voices are either silenced or ignored”

Inua Ellams, Cutting Through (in The Good Immigrant)

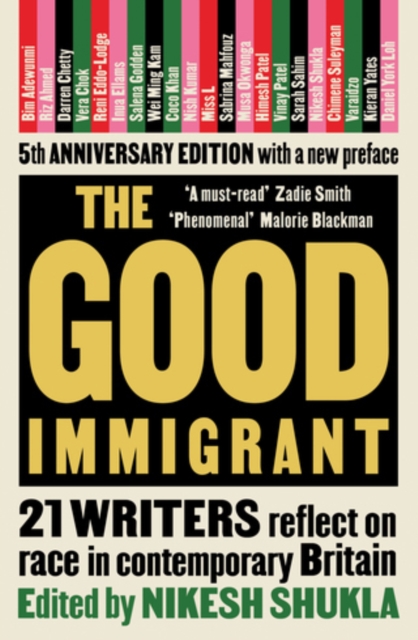

I am reading this great book right now, and I’d encourage everyone – not just those from ‘minority races’ – to get a copy.

That line from Ellams hit hard and reminded me of this incident in one of our PhD programme’s work-in-progress sessions where a colleague was presenting a chapter of their work, which attached the descriptor “a fan of colour” to quotes from interviewees. This distinction was important in the work because they were making a point about the voices of “people of colour” in a white-dominated fandom.

I did ask, however, why they opted to describe the individuals as “fans of colour” (to anonymise identities) and not, for example, just describe where they came from or what they identified with. I would, for example, always prefer to be referred to as Malaysian rather than a BAME person (Black and Minority Ethnic, as is so often used in the UK). They paused for a moment and said, it’s not something that they had thought about before.

Which, to me, is a good enough response – that’s the purpose of these WIP sessions anyway. I acknowledged this, saying perhaps it’s something to consider and tried to explain why I felt so. But their supervisor – a white person who was also chairing the session – cut me off and said (I paraphrase), “I don’t see a problem with using that phrase” and proceeded to call on the next person.

I was mortified to be called out like that in the room. For one, what is academia without discourse. But more significantly, I was extremely offended that my voice as a ‘BAME’ was shut down so quickly by a white person in a position of power.

I think back to that incident because I still feel that I didn’t articulate well enough why I thought my colleague should reconsider her phrasing. In discussing the diversity of communities and cultures that make up ‘black’ people in England, Ellams so articulately wrote: “Despite these obvious nuances, phrases like ‘black-on-black crime’ or ‘black community’ are used to suggest a monolith, it is portrayed as dysfunctional, rebellious, animalistic and mutinous.” Part of me wishes I was this articulate about the conflation of identities in making my point.

But I think also of what is happening in the US at the moment, where according to Ellams, the term ‘black’ was “an act of defiance, self-identification, and as a way to distance themselves from the ‘African’ label, which had abundantly negative connotations at the time”.

I think of the anger I’ve been feeling over the past couple of weeks at the injustice surrounding ‘people of colour’ in Malaysia, the UK, US and around the world, and the number of white people – my friends – who have responded with “not all white people” or “this doesn’t affect you” and more.

I think about how they have to just be better. Not just ‘white people’ but anyone who wields power and have utilised that privilege to silence minority voices. Over the past couple of weeks, the Malaysian authorities have been hauling up ‘illegal’ migrant workers, leading to clusters of Covid-19 infections among those communities – and many people think this is a good thing.

This is not a passive aggressive post – this is me calling you out.

Racism isn’t just about violence against people from other races. It’s not just about lynching, about hurting. Staying silent, silencing people, perpetuating systems of injustice, making excuses for other people’s microaggression – these are acts of violence too.

It’s not enough to just be not racist, or a bad person. But can you be a better person? ‘Fans of colour’ isn’t necessarily wrong or offensive, but is that enough? When you have the power and opportunity to craft your own words – and the privilege of the PhD viva to defend your decisions – why not opt to see these people. To give them a voice. To elevate their identities. To humanise them. Especially if the critical premise of the discussion is that these are marginalised voices in a white-dominated fandom.

Not being racist is not a passive act. Not being racist requires action – whether it’s speaking out against oppression, defending others in the face of injustice, and calling all of these out. That’s what we mean when we tell you that you have to be ‘anti-racist’, instead of just ‘not racist’.

It will be difficult, and uncomfortable, no doubt, but that is the every day reality for many ‘people of colour’. So, what can you do? Lots of people are already sharing things online. Keep at it, even if you feel like you’re alienating your audience (that discomfort you’re feeling is theirs too so normalise your speaking out). But more than that, call out any injustice you see in your daily lives (especially if you’re in a position of power), actively defend anyone being treated unequally, write to your MPs and other politicians, send letters to the editor, donate to groups working on the ground (yes, share your wealth).

As far as what is happening in the US is concerned, donate if you can afford it. I made a small contribution to the Minnesota Freedom Fund a couple of days ago to help bail out protestors who are being arrested. But they’ve been overwhelmed with responses and have suggested other organisations to donate to: read for details if you can help https://twitter.com/MNFreedomFund/status/1266053143512653826

Do better friends. And actively fight against inequality and injustice. In solidarity. ✊

Note: I originally wrote this for Facebook but decided that I should post it up here too. So there was never a title for this; instead, I chose a line from the article which best reflected my intentions although it makes no sense without context.